Issue 3 (84)

| THEORIES OF ETHNOGENESIS AS A SCIENTIFIC HERITAGE: THE CASE OF THE ACADEMIC HISTORY OF YUGRA | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 2024 | Number | 3 (84) |

| Pages | 80-89 | Type | scientific article |

| UDC | 39:94(571.122) | BBK | 63.5+63.1(253.3) |

| Authors | Golovnev Andrei V. |

Topic | ARCHAEOLOGY AND ETHNOGRAPHY OF NORTHERN EURASIA |

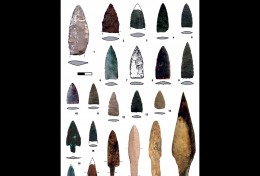

| Summary | The scientific heritage includes, in addition to fundamental discoveries and significant achievements in the applied sciences, important discursive themes of research and knowledge opened by science for society, the so-called “eternal questions”. These include ethnogenesis, the place of which differs significantly in Russia and in the West. In domestic science, it has always been one of the priorities, and in foreign one it was considered as a peripheral subject. The reasons for this discrepancy are rooted in the circumstances of the formation of the sciences: Russian ethnography took shape in the 18th century, as knowledge about peoples, Western anthropology — in the 19th century, as knowledge about human and humanity. Approaches to genesis differ accordingly: in Russian ethnography it is the origin of peoples (ethnogenesis), in Western anthropology it is the origin of humans (anthropogenesis). The study of the origins of peoples became one of the first achievements of Russian ethno-studies in the 18th century, and in this sense, ethnogenesis can be valued as the original scientific tradition of Russian ethnography. During the crisis of ethnography in the USSR at the turn of the 1920–1930s ethnogenesis served as a refuge for ethnography, condemned to be written off from the category of sciences for its inability to integrate into the concept of Marxism. The “Era of Ethnogenesis” brought impressive results, ensuring the leadership of Soviet ethnography in the study of ethnogenesis and ethnohistory. This can also be read in the historiography of the ethnogenesis of the Uralic (including Ugric and Samoyed) peoples, recently summarized in the Academic History of Yugra. The author’s contribution to the ethnogenetic discussion can be considered the presentation of ethnogenesis not as the secession of peoples, but as the distribution of activity niches between them in a multiethnic community (ethnocenosis). | ||

| Keywords | scientific heritage, ethnogenesis, ethnography, anthropology | ||

| References |

Akademicheskaya istoriya Yugry [Academic History of Yugra]. Khanty-Mansiysk: “Novosti Yugry” Publ., 2024, vol. 1. (in Russ.). Akademicheskaya istoriya Yugry [Academic History of Yugra]. Khanty-Mansiysk: “Novosti Yugry” Publ., 2024, vol. 2. (in Russ.). Alymov S. S. [Ukrainian Roots of the Theory of Ethnos]. Etnograficheskoye obozreniye [Ethnographic Review], 2017, no. 5, pp. 67–84. (in Russ.). Bloch M. Apologiya istorii ili remeslo istorika [The Historian’s Craft.]. Moscow: Nauka Publ., 1986. (in Russ.). Gillett A. Ethnogenesis: A Contested Model of Early Medieval Europe. History Compass, 2006, vol. 4, iss. 2, pp. 241–260. DOI: 10.1111/j.1478-0542.2006.00311.x (in English). Golovnev A. V. [Ethnography in the Russian Academic Tradition]. Etnografia [Ethnography], 2018, no. 1, pp. 6–39. DOI: 10.31250/2618-8600-2018-1-6-39 (in Russ.). Golovnev A. V. [New Ethnography of the North]. Etnografia [Ethnography], 2021, no. 1 (11), pp. 6–24. DOI: 10.31250/2618-8600-2021-1(11)-6-24 (in Russ.). Golovnev A. V. [Ethnogenesis as Solitaire Game: On the Origin of Samoyeds and Ugrians]. Etnografia [Ethnography], 2023, no. 3 (21), pp. 6–44. DOI: 10.31250/2618-8600-2023-3(21)-6-44 (in Russ.). Golovnev A. V. [Peter I and the Beginning of Sciences in Russia]. Kunstkamera, 2024, no. 1 (23), pp. 6–23. DOI: 10.31250/2618-8619-2024-1(23)-6-23 (in Russ.). Malinowski B. Izbrannoye: Dinamika kul’tury [Selected Works: The Dynamics of Culture]. Moscow: “Rossiyskaya politicheskaya entsiklopediya” Publ., 2004. (in Russ.). |

||

| Download in PDF | |||